We continue our profiles of Webb alumni by observing March as Women’s History Month and celebrating the achievements of WoW – the Women of Webb – and recognizing the barriers they have faced. Women have made significant contributions to the field of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) throughout history despite facing many obstacles and discrimination. Their hard work and determination serve as a model for us all, no matter our gender.

The maritime industry today provides more opportunities to women than in the past, but that transition does not happen quickly. Our first author shows us that women have been breaking barriers in male-dominated fields for decades.

Meet Monique (Mo) Sinmao. Mo manages wealth for high-net-worth clients, and raises capital for STEM-heavy businesses. She transitioned from engineering to finance and found that these two sectors share many common themes. She recalled her time at Webb where she gained real-life, tough experiences that prepared her for navigating through crises in her future career and life.

Mo’s story offers invaluable advice. She reminds us that STEM, and life, require a mindset of applied problem-solving and the willingness to take risks. She emphasizes the importance of a mentor and the benefits of a support system.

What inspired you to pursue a career in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math)?

We could have been stranded. Our new car broke down in North Carolina enroute to Disney World. Another driver behind us on the highway pulled up, fixed it, and sent us on our way, taking nothing in return. He was a mechanic and engineer for Chrysler and knew the exact design and production flaw. I think of STEM as applied problem-solving across categories, as shown by my family’s highway hero. After that, I immersed myself in how things work and not just how they turn on. I had four very different cars while at Webb, gas and diesel. My dad wanted to foster the attitude and capacity to fix anything. Then one day, while in the pit at Webb changing out a starter, two sets of professors’ legs walked by as they left the Diesel Lab discussing who they felt were natural engineers. Not one female student was mentioned. I sensed a lack of support. My heart could sink or inspire my STEM drive even more. This underdog chose the latter.

What did you plan to do with your degree from Webb?

My first goal was shallow and predictably local (Washington DC): find the most difficult engineering program and work for the military. After the graphic media coverage of damages to Prince William Sound following the Exxon Valdez oil spill (my senior year in high school), I took a broader interest in ship design. What are the specifications of a double hull to be sufficiently protective? What are the design and operational consequences?

And, profoundly, what is a “rock” or “grounding scenario” so that we can even define failure sequence and damage thresholds to withstand? After all, crash test dummies conjure common accident scenarios defined for autos.

It took Webb and then MIT to join ship structural design with operating environment modeling, using kinematic theory – solidly back to STEM.

Bringing Tech to the High Seas: Mo shares her expertise and wit as a speaker at Marine Money Asia – inspiring the industry to embrace the latest technological advances.

Do you think Webb prepared you well for real-life experiences?

No college prepares you for the range of “black swans” (unexpected experiences) like Webb. I chose Webb over MIT undergrad for being the most difficult engineering program considering the intense curriculum, grueling work requirements, resource density per student, Honor Code, and demanding immersive campus culture.

My Sea Term on a NASSCO-built oil tanker was a major milestone experience. I bungeed into a cargo tank to inspect structural damage after a grounding event. We flipped from the idyllic East Coast/St. Croix route to a winter North Atlantic crossing when the Iraqi military suddenly set fire to oil wells at the onset of the Gulf War in January 1991. We hauled equipment lines in gumby suits (green neoprene exposure suits with two fingers per hand). I watched 40-50’ waves swallow the entire bow of our tanker on bridge watch in the Bay of Biscay (aka Graveyard of Seafarers).

Despite the stormy conditions, Jeanne (a classmate) and I managed to draft our ship schematics. Our superstitious Captain blamed the women on board for the storms and gave me a poor review; I got an A+ from Professor Rowen.

Fast forward to my future career on Wall Street: boiler rooms and financial crises – no matter how “great” – were just another Sea Term to navigate through.

You also transitioned from engineering to finance, but still in the STEM field. What made you change course?

I have transitioned titles and fields but what I do at the core has not changed. Many seemingly distinct careers share the ethos of core engineering such as systems analysis, risk management, and prediction. Setting aside degree labels, I began to understand the essence of what I was becoming good at is decision-oriented analysis with incomplete inputs, dynamic systems, and risk-adjusted outcomes.

Finance and engineering share common toolkits like coding, regression analysis, feasibility analysis, and quantitative modeling. Engineering practice, where we regularly break things to understand limits, has been a powerful tool in finance where practitioners often rely on equations to measure risks without first dissecting the equations’ limits.

Most people would say the 2007–2008 financial crisis, or Global Financial Crisis, was caused by toxic mortgage-backed securities blowing up and taking down the global financial system. In reality, only the thinnest slice of mortgages blew up. What happened was the risk models (used to price mortgages) first underpriced risk and then grossly overpriced all classes of risks, due to how the models factored in contagion. Those who understood the fragility of the equations, versus real risk, made 8-10x returns by buying back the seemingly deeply impaired securities.

What do you find most rewarding about your work?

Today I manage wealth for high-net-worth clients. Like Webb’s endowment, which is managed to provide long-term funding for the school and its students, I manage complex return and liquidity needs sustained over generations of family wealth. I previously managed money for institutions in a range of roles and investment styles. Managing private wealth is more challenging, and also more rewarding, due to the human element.

By steering clear of Wall Street institutional roles, I can now engage in building and raising capital for startups without conflict of interest. I am at heart an engineer, a builder if you will – previously building teams with behemoth companies and now creating the concept and teams from inception. In this role, I have gravitated to STEM-heavy businesses that touch financial engineering, risk management, blockchain, sustainability, cryptographic securities, and regulation. The work is never done at startup/emerging companies, and it is rewarding working with high caliber individuals with a kaleidoscope of skills, with innovation in their DNA. Occasionally, the work revisits maritime (and Webbies) which is a bonus for me.

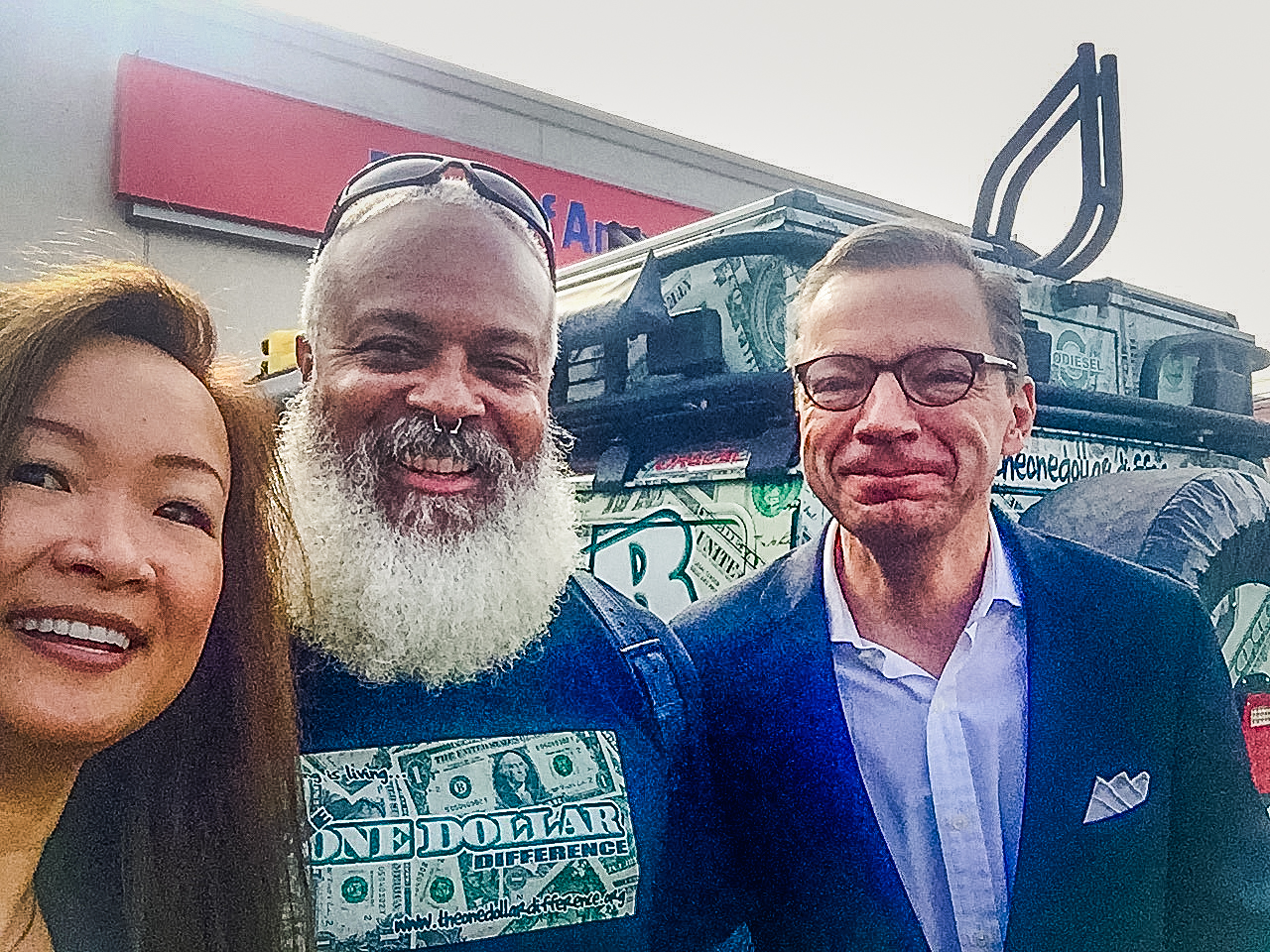

Capturing the Moment: Mo meets Wall Street’s legendary trader, Peter Michael Tuchman, capturing a moment as she pursues her own success in the world of finance.

Have you had any mentors or role models who influenced your career?

Three people strongly influenced my career.

When I was 12, one teacher nonchalantly suggested I take a test when I returned from vacation. I scored well, got a certificate, and visited my first college. It turns out this was an SAT test. I was nowhere ready for college, but her challenging advice allowed me to get into Thomas Jefferson High School for Science & Technology, which prepared me well for the pressures of college.

After Webb and MIT, I set my sights on business school at Georgetown where my dean, professors, and classmates all had discouraging advice regarding a naval architect’s prospects on Wall Street. My capstone project advisor, Christine Brennan at Oxford University’s summer program, said you’re really good at this so stick with it. Turn by turn, I steered my skills into a coveted corner of the job market where only 2% women land hedge fund portfolio manager seats. Years later, one Georgetown professor saw my progress on LinkedIn and wrote that my experience helped him revisit how he works with future students.

Finally, my first job on Wall Street was at Lehman Brothers. My first boss, Chip Dickson, remains a friend 23 years later. He took a risk on my engineering background, allowing me to analyze the most complex financial institutions in the world. Compared to most goods and services companies, the financial engineering in these companies starts at the deepest end of the Ocean, from zero. He warned me that once I could read financial statements and understand the global financial system, I would never see the world the same way again. He was right.

What do you think can be done to encourage more girls and young women to pursue careers in STEM?

Foster interest in asking questions, try things out, dialog: all are important. One good thing leads to another. Those people who took risks on me motivated me to take risks for myself. Taking risks is essential to developing skills and focusing your time on building those skills. Risk-taking and feedback are an on-going iterative process.

Providing nonlinear perspectives can be illuminating. STEM does not crowd out or exist apart from other interests. Before STEM, I found my way first to creative writing, literature, art, and performing arts. STEM switched the light on for other dimensions of these other interests. In poetry and music, there is math. In classical and Hawaiian dance, the instruments, sets, and costumes involve design, engineering, and technology.

What advice do you have for Webb students on life after graduation?

Make thoughtful and honest decisions for yourself. For success and happiness, aim for the intersection between what you love doing, what you are committed to becoming excellent at, and the kinds of people you want to be around. Even when way off course, one of those three will lift you.

Own your path. The things that stand between you and your goals won’t be unique to Webb. Don’t depend on others – family, faculty, and friends – to remove roadblocks for you; practice coming up with solutions and invite their feedback to find your path around obstacles, work your way to a stronger position, and fix the things you care about.

Your own validation is powerful. People won’t always understand your strengths and weaknesses along the way. Sometimes you have to cheer yourself on until your results are fully baked for others to see.

Adventuring the Great Outdoors: Mo braves the element on a glacier, posing for a photo with a snow automobile in the background.

Riding in Style: Mo shows off her playful side as she takes a ride on a motorcycle with a carrier looking effortlessly cool.